Concept-Based Learning with Year 7 Historians on the Silk Road

‘Concepts are a kind of mental glue, then, in that they tie our past experiences to our present interactions with the world, and because the concepts themselves are connected to our larger knowledge structures’.

The Inspiration

I remember feeling distinctly underwhelmed on results day. I'd got my place at university, my parents were celebrating egregiously, and yet, I thought to myself, what do I really understand about anything? At the time I knew how to determine the price-elasticity of demand (now gone) and how to integrate a quadratic function (definitely gone) but how did all these bits and pieces fit together to help understand life, the universe and everything? That feeling has never gone away. The more I learn about Concept-Based Learning (CBL), the more I wish I’d had the benefit of such an approach when I was at school.

The goal of CBL is to equip students with a powerful and flexible conceptual framework (or schema) that will enable them to Live Worldwise. Rather than amass disposable bits and pieces of knowledge to pass an assessment, students are guided to see underlying relationships between concepts. This empowers them to use existing schema to interpret, organise and generate meaning in new contexts. Such an approach encourages students to be reflective learners, probing and refining their schema to consider its validity in the light of new information. It also promotes student action by placing transfer to real-world contexts and authentic assessment at the heart of the process. All of these valuable, integral aspects of CBL clearly link with existing ‘literacies’ at Dulwich College (Singapore); CBL has the potential to unite what can seem like disparate strands into a cogent whole.

I was inspired to learn more about CBL theory and process by Julie Stern. Stern, founder of Learning That Transfers, and a leading advocate of CBL, introduced her key ideas to staff in two training sessions in September 2021; she has since continued to advise the Senior School’s Conceptual Education Steering Committee.

I had some initial doubts about CBL:

‘I teach concepts anyway so this training probably won’t apply to me.’

‘We already have reviewed, robust curricula in place so why go tinkering again?’

‘This all sounds very MYP to me and we’re an IGCSE school so probably not a good fit.’

Yet the potential of CBL seemed so great that I still wanted to explore what it might mean in practice, and whether it would work, at the College. I am glad that I did because all of my initial prejudices were proved wrong.

Getting Started with Concept-Based Learning

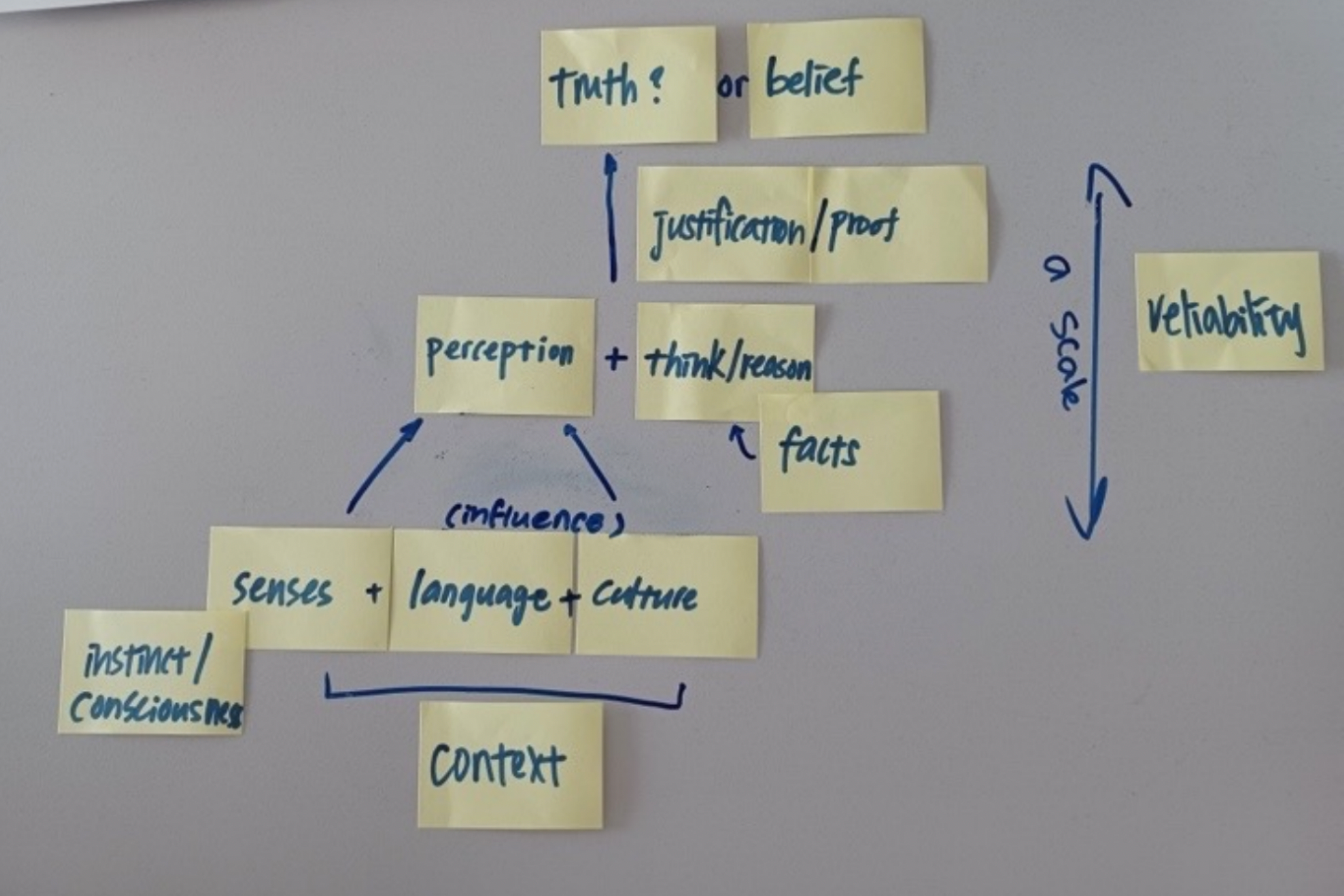

An easy way to get going with conceptual learning is to start with a single lesson and use some of the free, tailor made resources at Stern’s Learning That Transfers (LTT) website.2 This has a series of tools and activities that facilitate the Acquire, Connect and Transfer (ACT) model. Students must gain a solid understanding of each concept before they can consider conceptual relationships or test these in new contexts. The day after Stern’s Personal Learning Development (PLD) session, I taught a Year 10 History lesson on the impact of Nazi rule on German women. I start this topic with propaganda images that provoke an exploration of the Nazi feminine ideal (‘concept attainment via sorting’ in LTT-speak). We usually then analyse the impact of relevant government policies. On this occasion however, I asked students to consider the relationship between relevant concepts: ‘gender’, ‘feminine’, ‘propaganda’ and ‘stereotype’. These were written on Post-it notes, then arranged and connected by the students in a meaningful fashion. I asked questions such as ‘how are gender and stereotype connected?’ to guide the creation of generalisations, statements of conceptual relationship that can be used to create meaning in new contexts. We then considered how far the generalisations applied at Dulwich College (Singapore) and in contemporary Singapore (a process called ‘expansive framing’). I used a similar approach to unpack the meaning of ‘knowledge’ in a Year 12 Theory of Knowledge (TOK) class (Figure 1): having acquired key concepts, we considered questions such as ‘What is the relationship between knowledge and belief?’, and ‘What effect do language and culture have on perspective?’. This helped students to engage in, and articulate ideas about a notoriously esoteric topic. These were interesting and thought-provoking activities; I would certainly recommend using the LTT resources if you want to get started with CBL.

Figure 1: Post-its used to explore knowledge-related concepts in a Year 12 TOK lesson.

Next steps with Concept-Based Learning

If you tried and enjoyed the LTT lesson tools, then the next step is to explore the rest of the website, or ideally read the latest book3. It carefully takes you through all the key elements of CBL: its rationale, practical ways to use it in lessons, and how to create effective units or even whole courses. Many ideas in the book lean heavily on the earlier work of H. Lynn Erickson and Lois A. Lanning4, but the LTT book is more accessible and offers a more time-efficient approach to planning. Having done my research, my next step was to adopt a CBL approach to a whole unit.

CBL units have an internal coherence based on ‘anchor concepts’, but they are clearly integrated into a whole course through the use of ‘disciplinary lenses’. These are a range of 1-5 overarching concepts that students will revisit on multiple occasions throughout the course. For the Years 7 and 8 history course we have the ‘disciplinary lenses’ of power, change, significance and perspective. I decided to use these and start with a two-week Year 7 history unit on the Silk Road.

I roped in some colleagues to help review the scheme of work. The key question was ‘What organizing concepts bring coherence and meaning to this content?’5. This was a stimulating conversation that I can highly recommend for a future departmental meeting. The most appropriate anchor concepts that emerged were ‘trade’, ‘network’, ‘culture’ ‘exchange’ and ‘travel’. We then drew up a list of conceptual relationship questions such as ‘How does travel affect culture?’, ‘How are trade and exchange related?’, ‘What is the relationship between trade and network?’. Stern recommends creating somewhere between five and nine such questions per unit. You can also plan to ask some ‘debatable questions’ that will expose and stretch students’ understanding of the anchor concepts, for example, ‘Can you be wealthy without cash?’ and ‘Was trade the most important reason to travel in the past?’. In the first lesson we acquired and connected the anchor concepts in the context of Singaporean history which most students had covered in the Junior School. Only then did we move on to the dissimilar context of the Silk Road.

Having established the conceptual focus, the next stage was to plan an authentic assessment in a dissimilar context. Students were informed that they would work in groups to design and create a peer-appropriate game that explored some of their generalisations in the context of Silk Road history. Armed with a teacher-led overview of the facts, and access to further, curated resources, the students set to work on their games. I circulated while the groups worked and asked students which generalisations would feature in their game. Students were asked to monitor their progress to prepare for a final reflection; in my own reflection, I noted this would have worked better had they kept a brief learning journal during the project. If they completed their game before the final lesson, students could request ‘beta testers’ to play their game and provide formative feedback. In the final lesson, the students played each other’s games and rated them on levels of fun and how far they helped explore key generalisations. Students were then asked to reflect on the success of their game in light of a culminating discussion.

Figure 2: Year 7 students enjoying a Silk Road game.

In an ideal world, students would have already experienced the acquire, connect, transfer model so they could more have more independently and successfully created and revised generalisations. They would also have had more time to reflect on the advancement of their conceptual understanding, rather than just their teamwork, or how fun their game was. Overall however, this was a rewarding experience and one that I plan to repeat with another unit before the end of the academic year.

How far could Concept-Based Learning work at Dulwich College (Singapore)?

Stern advocates an iterative process that explores the same generalisations through a series of increasingly dissimilar contexts, one directly after the other (for example, ‘What does it mean to be civilized?’, explored in Ancient Greece, Medieval Europe and contemporary India). There is clear value in dissimilar transfer but there are also clearly time implications. There is an argument to reduce the number, and increase the length of units in Years 7 and 8 to facilitate CBL. This is not an option with our IGCSE and IB cohorts. However, the IBDP already has ‘Key Concepts’ whose use as ‘disciplinary lenses’ could be fruitfully reviewed. While IGCSE courses lack overt conceptual framing, we enjoy the luxury of having three years to cover a two-year syllabus. An excellent way to use some of the extra time would be to review our curricula and introduce more CBL elements.

I am yet to be convinced that Stern’s desired approach would promote learning in sufficient depth to access top grades in external examinations. I would envisage a longer-term iterative process, with the same generalisations revisited in different contexts as they arise in the curriculum. In IGCSE History, students will encounter concepts related to women, equality and society later in Year 10 when we consider Second-Wave Feminism in the USA, and again in Year 11 when we explore the impact of Mao’s rule on Chinese women. Approaching these topics with CBL in mind will also support ‘distributed practice’ that has proven benefits for long-term learning retention.

At a time when Global Citizenship is emerging as a core component of a Dulwich education, there has never been a better incentive to get to grips with CBL as a driving force in our teaching and learning: Global Citizenship could, and in my view should, provide the highest framing concepts from which all disciplinary lenses take their lead. Revisiting a unit or a whole scheme of work with ‘disciplinary lenses’ forces consideration and discussion of the most important questions in teaching: ‘Why are we teaching what we teach?’, and ‘What do we want our students to understand at the end of this?’. If we want our students to truly Graduate Worldwise then we must build in rather than bolt on Global Citizenship to our curricula. Concept-Based Learning is a powerful tool to help us accomplish this task.

Works Cited:

Erickson, H. Lynn, et al. Concept-based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom. 2nd ed., Thousand Oaks, Corwin Sage, 2020.

Murphy, Gregory L. The Big Book of Concepts. Cambridge, Bradford Books, 2004.

Stern, Julie Harris, et al. Learning That Transfers: Designing Curriculum for a Changing World. Thousand Oaks, Corwin, 2021.

Website:

Learning That Transfers. learningthattransfers.com/resources/. Accessed 8 Mar. 2022.